Boom and Bust: Population Cycles in NH's Wintering Birds

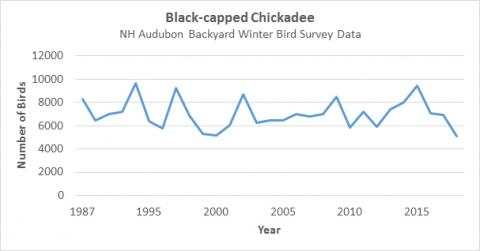

Those of you with bird feeders may recall two broad themes from the winter of 2017-18: there were fewer chickadees and a lot more juncos.

Hardly a day went by without a call or email to NH Audubon, NH Fish and Game, and UNH Cooperative Extension from someone worried about the absence of chickadees.

The question would also regularly surface on email lists and social media. Did they all die off? Migrate away? And why are there are so many juncos?

As a population biologist, I’m never one to focus on a single year as indicative of anything terribly catastrophic (but ask me about chipmunks sometime), and the trends we observe are part of patterns that play out over multiple breeding seasons. It’s easier to get this perspective when you have several years of data to peruse, and here at NH Audubon we have such a data set. The Backyard Winter Bird Survey (BWBS) started in 1987 as an expansion of previous cardinal-titmouse-mockingbird survey. Every February over 1000 volunteer observers watch their yards and let us know what they see – and I get to play with the data to look for patterns.

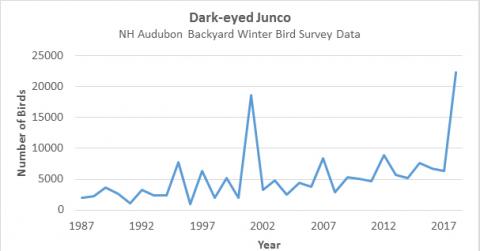

During the 2018 BWBS, chickadees actually hit an all-time low (5076) and juncos an all-time high (22,303). Also setting records were Wild Turkey (2876), Red-bellied Woodpecker (727), Common Raven (111), Red Crossbill (20), and Gray Squirrel (5579). Each species has a different story to tell, but all but the raven and woodpecker are linked by a common theme: food. Food supplies can work in one of two opposing ways to influence bird populations. If there is a lot of food birds may experience higher breeding success, and there are simply more birds around as a result. Alternatively, migratory species may shift around to concentrate where food is plentiful and avoid areas with less bounty. The graph below shows the number of juncos recorded on the BWBS over time, and you can see that they’re pretty stable around 5,000 except in 2018 and 2001. In both those winters, the preceding fall was marked by an abundant natural seed crop (in this case weeds and the like in shrubby fields and roadsides), and an analysis I did in 2001 suggested that juncos simply didn’t migrate as far south as usual. Christmas Bird Counts in the southeastern U.S. recorded below average numbers while we had lots up here in New England.

The fall of 2017 also produced bumper crops of acorns, berries, and cones (this periodic abundance of fruit and seed is called “masting,” and it’s not usual to have most plant species doing it at the same time. Like the juncos, some birds responded to abundant food by staying around, while others exhibited higher survival or actually moved into New Hampshire from somewhere else. Wild Turkeys and Gray Squirrels spent the fall eating the bumper crop of acorns, and as these ran out they turned to feeders. The squirrel carnage along New Hampshire’s roads in the fall of 2018 is directly related to all this via high reproduction coupled with an absence of oak mast: squirrels need to find food somewhere and roads are in the way. Crossbills and other northern finches will cross the continent when there’s a cone failure in one region and a mast in another, and they did just that starting in the summer of 2017. With the cones all gone, the crossbills have turned their nomadic sights elsewhere – and who knows when they’ll show up here again. When you’re tracking food supply on the continental scale, the Granit

This is all well and good, but why then were there so few chickadees? One possibility is that, like the juncos, some chickadees that usually move south from Canada simply stayed put farther north. The limited analysis I did for this question doesn’t quite bear that out, so we’re left with either an actual decline or some other version of a spatial shift. Although we really don’t have the data to separate these two, there were plenty of anecdotal data from this past winter that suggested chickadees were simply not coming to feeders as often. Birders found them deep in the woods foraging on cones high up in White Pines, and researchers located individually tagged chickadees well away from the residential areas they usually frequented. If these observations are indicative of the larger pattern, then the population didn’t decline precipitously at all. It also shows you that our winter birds are far less reliant on our feeders than we think they are. Chickadees are back at feeders in the fall of 2018, based both on our own observations and the lack of panicked phone calls from the general public, so all is apparently back to “normal.”

Without a mast event this year, we can even predict with some accuracy what bird populations are going to do. I’ve already said that the crossbills are gone, but early indications are that redpolls will be here to replace them (thanks to the lack of birch mast in Canada). Blue Jays may be scarce, since without acorns more probably migrated south than usual. And thus these populations go up and down, down and up, and it falls to us to simply sit back and enjoy the complex workings of our local (or continental) ecosystems – right out our living room windows.

People interested in helping NH Audubon collect data on winter bird populations are encouraged to participate in the annual Backyard Winter Bird Survey on February 9-10, 2019.

More information is available at: http://www.nhaudubon.org/backyard-winter-bird-survey/.