The Future of Beech in New Hampshire

A new forest pest is being found throughout New Hampshire, and it is causing concern for the health of New Hampshire’s beech trees. You may have heard about beech leaf disease as www.NHBugs.org has received reports indicating that it has been found in over 100 NH towns.

This new disease, coupled with beech bark disease which has been affecting New Hampshire’s forests since the 1960s, is threatening the future of this native tree species. This long-lived tree is ecologically important, providing food and protection for a variety of wildlife species. It is unclear how our landscape and the wildlife that depend upon it will be impacted as this new pest combines with the old one. Let’s take a look at beech trees in New Hampshire’s forests.

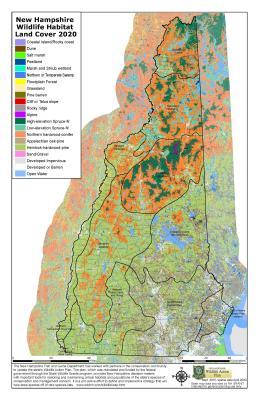

The burnt orange color in the NH Wildlife Action Plan Habitat Land Cover map illustrates the extent of the northern hardwood forest habitat, while the pale green identifies the Pine-Hardwood-Hemlock habitat type.

Beech is a significant species in New Hampshire’s forests

American beech is a foundational species in our northern hardwood forests which encompasses approximately 20% of the state’s forest land. Beech is also an important component in our hemlock-hardwood-pine forests which cover roughly half of the state. These habitat/forest types are described in the NH Wildlife Action Plan and more information can be found in the Habitat Stewardship Brochure Series.

Beech Ecological and Economic Values

Beech trees are capable of living 300-400 years. Our northern hardwood forests are comprised of American beech, yellow birch and sugar maple, along with other species including red maple and white ash. Spruce and fir are often mixed in at higher elevations and further north in the state, while hemlock, white pine and red oak are found together with beech more frequently at lower elevations and in more southern areas of the state.

Beech is a shade tolerant species. It can become established in low light conditions, waiting patiently in the understory for a disturbance to provide more light.

American beech is a great source of firewood, it is moderately easy to dry and split, has a good density, and provides a medium burn length. Beech is also durable and is used to make the timber mats you often see as utility companies move equipment across wet areas. While beech can be used for other forest products such as furniture and flooring, we don’t have significant markets for beech lumber.

Beech is important ecologically in the landscape as it provides a good food source for wildlife (beechnuts), and also develops good cavities giving shelter to many species.

Beech leaf and nut husks

Beech trees begin producing a substantial volume of beechnuts when they reach about 40 years old, and by the time they are about 60 years old, they can produce large quantities of nuts. Good nut crops are produced at 2 – 8 year intervals.

Beechnuts are rich in carbohydrates and fat and they are an important fall food source for bears. Food availability can be especially important for the breeding success of female bears. While bears mate between early June and mid-July, delayed implantation of the fertilized egg occurs in the fall if a female bear reaches a minimum body weight.

A study in Maine found that where beechnuts were an important fall food source, good beech seed years resulted in approximately 80% of females producing cubs the following year. In poor beech seed years, only 22% of female bear produced cubs the following spring. Where there were other good fall food sources available, the poor beech crops had less of an influence.

Beeches are also important when it comes to supporting a variety of insect populations. The National Wildlife Federation identifies beech as being one of the top 30 Keystone Plant Genera for Butterfly and Moth Caterpillars in the Northern Forests. This is important as insects are an important food source for growing baby birds.

Beech trees offer abundant opportunities for wildlife that use cavities for nesting, roosting, and denning. With their dense wood and relatively slow ability to compartmentalize against decay, beech tree cavities and snags can remain available for wildlife for long periods of time.

Beech Leaf Disease

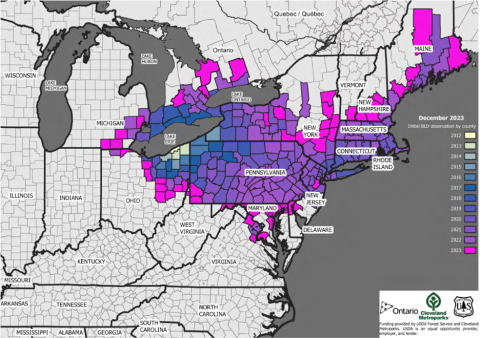

Beech leaf disease (BLD) was first identified in Lake County, Ohio, in 2012. Since then, it has been spreading eastward across the US. It was first detected in New Hampshire in 2022, and has now been found in over 100 NH towns. BLD likely originated in Japan, though it does not appear to cause significant tree mortality there.

The first symptom of beech leaf disease is dark banding on beech leaves between the leaf veins. This banding is evident early in the spring. As symptoms worsen, you may see heavier banding, as well as shrunken, crinkled, thickened, or leathery leaves. You may also see more yellowish banding later in the season. Severe cases result in aborted buds and premature leaf drop, leaving trees with thinner canopies over time. Serious decline and mortality of beech appears to take 3-6 years depending on the vigor of infested trees.

Beach leaf disease impacts American beech as well as several ornamental beech species. The disease is caused by microscopic nematodes Litylenchus crenatae mccannii that damage the inner tissue of leaves and inhibit their ability to photosynthesize. The disease damages leaf buds which leads to leaf loss, canopy thinning, and aborted buds. Beech leaf disease has killed a large number of beech trees across the eastern United States.

The nematodes (females, juveniles and eggs) spend the dormant season in tree buds. We see the symptoms in the affected leaves throughout the spring and summer as the nematode populations increase. In the late summer and early fall, the nematodes migrate from the leaves to the newly forming buds. Both wind and rain appear to play a role in the spread of these organisms, and researchers are continuing to study this disease.

There is no recommended treatment at this time and research is ongoing to determine the mode of spread. Transportation of live beech plant material should be severely limited.

If you think you have seen beech leaf disease, please visit https://www.nhbugs.org/damaging-insects-diseases/beech-leaf-disease to report it.

Beech leaf disease. Note the dark bands on beech leaves between the veins.

Known range of Beech Leaf Disease, from initial observation in 2012 to its current reach expanded annually by county. Map courtesy of Cleveland Metroparks with USDA Forest Service cooperation.

Beech Bark Disease

Most people have come to recognize the tell-tale symptoms of beech bark disease. While healthy beech trees have smooth gray bark, the bark of those infected with beech bark disease is heavily pockmarked with patches of dead tissue and fissures. Beech bark disease involves the introduced beech scale insect along with two fungi that collectively weaken and kill beech trees. The beech scale insect, Cryptococcus fagisuga, was mistakenly introduced to North American from Nova Scotia in the 1890s. It was first detected in New Hampshire during the 1950s and 1960s.

The beech scale is a tiny insect that uses its piercing mouthparts to penetrate the bark and feed on the phloem tissues of the tree. The insect feeding sites allow two different species of fungi (Neonectria faginata and Neonectria ditissima) to get through the protective bark layer. Much like skin on our bodies, tree bark protects the inner tissues from damage. Once that protective layer is breached, infections and diseases can infect the host.

The Neonectria spp. kill the beech tissue and create cankers. As those cankers expand and coalesce, they can girdle the trees.

Healthy beech tree. Photo Courtesy of Joseph O’Brien, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org.

Beech tree with beech bark disease

As Beech Bark Disease (BBD) has expanded from Nova Scotia to the south and west, the disease has been associated with three stages: the advance front, the killing front and the aftermath forest. In NH, we are now working with the aftermath forest.

Beech bark disease, in addition to causing mortality in some trees, causes chronic stress and reduced growth rates (reductions of up to 40%) in others. Beechnut production is also reduced, with impacted stands producing 40% fewer beechnuts than healthy stands. As trees die, dense thickets of beech root sprouts can take over the available growing space in the forest, reducing diversity.

As beech leaf disease moves east, it is coming into contact with the beech bark disease aftermath forests. If the experiences of those in the areas that have been monitoring beech leaf disease the longest are to be expected here, we will likely see more beech mortality. This will create more cavity trees and downed material which will benefit some species, but we will see diminished levels of an important food source for others.

What can we do about it?

Foresters have been using group selection silviculture as a means of harvesting in northern hardwood forests to try to reduce the proportion of beech and increase the diversity of regeneration in northern hardwood stands. Group selection harvesting involves removing groups of trees from an area, often creating openings of ¼ or ½ acre up to two acres in size. By creating openings that are larger than those created by individual tree selection, group harvesting allows more light to reach the forest floor, letting more species become established and grow.

When healthy beech trees are found in the forest, foresters try to retain them during harvesting with the hope that they will continue to grow and produce BBD resistant seedlings. Somewhere between 1-5% of beech trees are believed to be resistant to beech bark disease. Bear clawed trees are also retained as they tell us that these trees are producing good beechnut crops. The claw marks show that bears are climbing these trees to reach the beechnuts before they fall to the ground. These trees are typically left for their wildlife value and so they may continue to produce seeds and seedlings.

Beech with claw marks

We don’t know whether trees that are resistant to beech bark disease will also be resistant to beech leaf disease, and it will be important to monitor trees to look for those that show resistance to beech leaf disease.

A good first step is to determine how much of a component of beech is in your forest, paying particular attention to the larger beech trees that are providing beechnut crops. Locate and identify healthy beech trees and monitor those trees. Evaluate species diversity on your land. What other tree species are present and what are they contributing in terms of wildlife habitat? Depending on the level of detail you want, you can do this evaluation yourself, or you can hire a licensed forester to help you conduct a more comprehensive inventory of your property and/or develop a forest management plan for you based on your goals.

As climate changes and growing seasons lengthen, some more southern species may be able to expand their ranges northward. For example, species such as white oak and shagbark hickory are found in southern New Hampshire. A number of landowners have been experimenting with planting these species as well as other species like American chestnut slightly north of where they are currently found. If successful, this offers more diverse food sources for wildlife in the future, and may help ameliorate the expected reduction of beechnuts. Planting shrubs such as hazelnut and beaked hazelnut also offer additional food resources.

The Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) is a cost-share program administered by the Natural Resources Conservation Service. This program can help cover the costs of developing a forest management plan and implementing a variety of practices such as planting fruiting trees and shrubs for wildlife, forest improvement practices to increase the quantity and quality of important mast (seeds, catkins, fruits, and nuts) sources for wildlife, and improving and sustaining forest health and productivity.

For questions or information about your forestland (approximately 10 acres or more) contact your County Forester. Extension foresters help landowners achieve their goals and identify potential stewardship opportunities through site visits, workshops, educational materials, woods forums, and field days. We can visit your property (~ 10 acres or more) for free, and help you achieve your goals for your property including forestry, recreation, wildlife habitat, water resources, scenic beauty, and more. Visit https://extension.unh.edu/countyforesters for more information.

There is a lot of research being done to look at these two beech diseases to determine how we can keep this important native tree in our landscape. There is promising research that may offer options for maintaining beech trees in more urban and suburban locations, but so far, we do not have good options for our forests.

Please report any signs of Beech Leaf Disease at www.nhbugs.org and click on the button to “Report an Invasive Insect or Disease”.

Sources:

- Beech Health Workshop. October 9, 2024 Fox Forest – Henry I. Baldwin Forestry Education Center, 309 Center Road, Hillsborough, NH.

- Cale, Jonathan A., Mariann T. Garrison-Johnston, Stephen A. Teale, John D. Castello. Beech bark disease in North America: Over a Century of Research Revisited. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2017.03.031 Forest Ecology and Management 394, March 2017 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0378112717301470?via%3Dihub

- DeGraff, Richard M., and Mariko Yamasaki. New England Wildlife Habitat, Natural History, and Distribution. University Press of New England, Hanover, NH 2001.

- Keystone Native Plants, Northern Forests – Ecoregion 5 - National Wildlife Federation, https://www.nwf.org/-/media/Documents/PDFs/Garden-for-Wildlife/Keystone-Plants/NWF-GFW-keystone-plant-list-ecoregion-5-northern-forests.pdf

- Jakubas, Walter J., Craig R. McLaughlin, Paul G. Jensen, Stacy A. McNulty. Alternate Year Beechnut Production and its Influence on Bear and Marten Populations. In: Evans, Celia A., Lucas, Jennifer A. and Twery, Mark J. eds. Beech Bark Disease: Proceedings of the Beech Bark Symposium; 2004 June 16-18; Saranak Lake, NY. Gen Tech. Re. NE-331 Newtown Square, PA: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station: 79-87.

- Burns, Russell M., and Barbara Honkala, tech, coords. 1990. Silvics of North America:2. Hardwoods. Agricultural Handbook 654. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Washington, DC, vol. 2, 877p.