Making Connections

We all know that connections are important. They’re important in business. They’re important for relationships. They’re even important for internet service. It’s likely that there are many people who haven’t thought about the importance of connections for wildlife – but, for those working to conserve and manage New Hampshire’s wildlife and habitats, these connections have become a primary focus in recent years.

New Hampshire is home to an incredible diversity of wildlife species – birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, beetles, bees, butterflies, and all sorts of other critters are sharing our landscape. They rely on various habitats – like forests and wetlands – to meet their basic needs. And, while these species come in all different shapes and sizes and have many differences, they have one thing in common – they move! Wildlife don’t stay in one place. Different species move various distances to find food and shelter, to reproduce, to migrate between seasonal habitats, and to disperse to new territories.

A wildlife corridor is a habitat linkage that joins two or more areas of habitat, allowing for the movement of wildlife. Providing these connections between habitats allows wildlife to move safely from one area to another. This is important to help reduce the risk of population extinction, maintain genetic diversity, and ensure that species are better able to adapt to our changing climate. Wildlife corridors can take different forms and vary in scale, depending on the landscape and wildlife species being considered, but can include forested areas, riparian areas, ridgelines, and even hedgerows. Wildlife crossings – areas where wildlife cross over or under the road surface – that connect priority habitat blocks are also really important for maintaining connectivity.

Maintaining and restoring connected habitats is critical for wildlife as our landscape changes. As human activity has and continues to increase in the New Hampshire landscape, roads, houses and other development can result in the direct loss of wildlife habitat and the remaining habitat becomes fragmented into smaller and smaller habitat blocks. The loss of wildlife corridors can result in direct mortality, barriers to movement, and habitat fragmentation for many species. The risks are especially high for slow-moving species (like spotted salamanders), species that depend on high adult survivorship (like Blanding’s turtles), species that are long range dispersers (like bobcats), and species that already have limited populations (like timber rattlesnakes). Luckily, there are many professionals, groups, and organizations working together to identify, manage, and conserve these connections in New Hampshire.

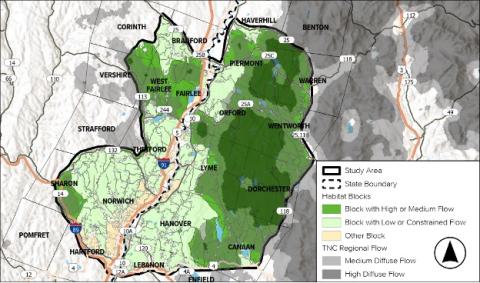

Some groups, like the Upper Valley Land Trust, are taking the initiative to learn more about wildlife corridors and identify important areas on a local level. The Upper Valley Connectivity Study is a project implemented by consulting ecologist Jesse Mohr of Native Geographic, and supported by professionals from Upper Valley Land Trust, NH Fish & Game, Vermont Fish & Wildlife, and Dartmouth College. Using a combination of remote sensing and on-the-ground studies in the form of tracking surveys and wildlife cameras, the project aims to identify opportunities and develop recommendations for protecting, restoring, and promoting ecological wildlife connectivity in the region.

The Upper Valley Connectivity Study is one example of a group taking a closer look at wildlife corridors in their region. Map provided by Jesse Mohr, Native Geographic.

“The goals are to find the most important places to conserve and protect for wildlife connectivity,” shared Jesse Mohr. “Upper Valley Land Trust owns a lot of land, and they want to know how to best steward their land for connectivity.” While analysis is still underway, the hope is to provide information to prioritize the habitat connections and wildlife crossings that provide direct and functional connectivity between large, unfragmented habitat blocks and core habitat areas. This study was funded in part by grants but requires additional funding through donations to complete the project. Upper Valley Land Trust has given the option to give directly to the Wildlife Connectivity Study on the Donate page on their website.

Towns, land trusts, and other conservation groups can all play a role in identifying these valuable connections for wildlife. If you’re interested in taking on a similar effort in your region, there are some resources available to help you get started:

- NH Wildlife Corridors Report

In 2017/2018, the NH Fish and Game Department partnered with the NH Department of Transportation and NH Department of Environmental Services to research wildlife corridors and address Senate Bill 376, which focuses on wildlife corridors. Efforts included identifying existing and needed corridors, voluntary mechanisms affecting corridors, and relevant statutes and regulations. Read more about that effort and access the report here.

- NH Wildlife Corridors Map

NH Fish & Game Department has developed a tool to help identify these important areas on the landscape. The maps include core habitats connected by habitat corridors and can be used to help inform conservation planning efforts. Click here to learn more and view the map.

- Wildlife Corridors in New Hampshire Brochure

The Taking Action for Wildlife team developed and printed a brochure to help others learn and communicate about wildlife corridors. These are available to groups or communities that might want to share them with landowners or other stakeholders. To request free copies, e-mail forest.info@unh.edu.