Every morning in late fall, I watch the sunrise over my neighborhood, ice crystals catching the sun’s rays. I am bearing witness to the world’s changes, through the turning leaves, the migrating geese, and the frost on the grass. These seasonal changes are welcome and familiar. Across the valley, on the opposite hill, I watch the construction of a water tower for a new development. I am also witnessing these changes, as human development inches on.

"Exurban” areas like my neighborhood lie between suburban and rural in terms of housing density. These areas are more sparsely populated, though you can probably still see your neighbors’ houses across the way. The United States is becoming more and more exurban. In New England, people are moving out of cities to less populated areas. This increase of human development in once-rural places means that both wildlife species and humans must adapt to their new neighbors. My research focuses on how wildlife species respond differently to development in predominantly exurban and rural areas.

A view from my back window of my neighborhood. This is what exurban development can look like. [Photo by Mairi Poisson]

The Wildlife Modeling and Management Lab at the University of New Hampshire is led by Dr. Remington Moll. The graduate students in our lab focus on the population ecology of furbearers, monitoring methods for moose, and deer fawn survival. My focus, as well as the research focus of some of my lab mates, centers on the impacts of human development on wildlife species. In one recent study, I had the privilege of collaborating with my lab mate, PhD student Andrew Butler, our advisor Dr. Moll, and partners at the New Hampshire Fish and Game to publish our research in the Journal of Urban Ecology.

Our study examined whether and in what ways 13 different mammal species altered their activity in response to human development. We used images from 104 motion-activated cameras, commonly called “trail cameras” throughout Southeastern New Hampshire to compare wildlife activity in exurban and rural areas. Eastern cottontail rabbits, snowshoe hares, Eastern striped skunks, fisher, Virginia opossums, red foxes, gray foxes, raccoons, North American porcupines, bobcats, coyotes, and white-tailed deer all traipsed in front of the lens of our cameras, providing us with data to analyze what times of day they are active and what levels of human development they are most active in.

Red fox, bobcat, fisher, and deer captured by a motion-triggered camera in southeastern New Hampshire. [University of New Hampshire, New Hampshire Fish and Game]

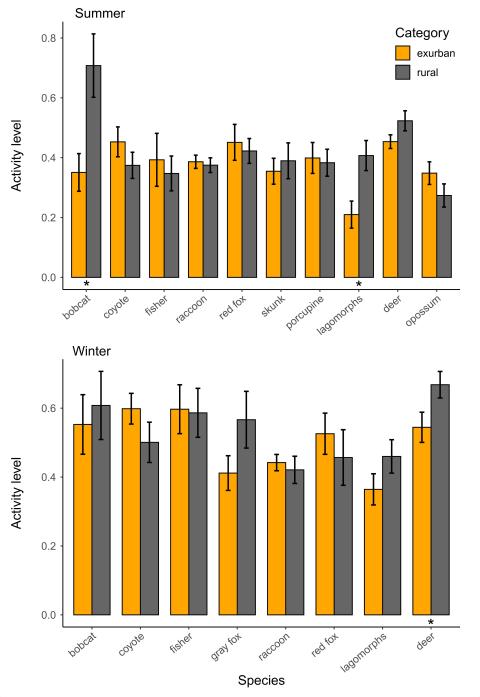

We examined both activity levels – the overall portion of the day a species is active – and activity patterns – the daily variation in a species’ activity – in the summer and winter of 2021 and 2022. In short, we found that responses to human development were species and season-specific. There was no universal response to human development by all of our study species. Some species reduced their activity levels in exurban areas, like the white-tailed deer, while others marginally increased activity, like the coyote.

Activity levels in rural and exurban areas during summer (top) and winter (bottom) for our study species. [Poisson et al. 2023]

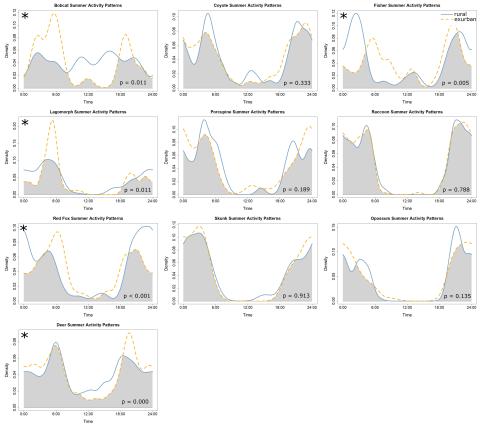

In terms of activity patterns, some species increased their nocturnal activity in exurban areas – which would be expected for species trying to avoid encountering people. During the summer, bobcats were significantly more active at night as compared to rural areas. However, other species shifted away from nocturnality and became more diurnal, like the fisher. There are many possible explanations for these divergent behavioral shifts. Perhaps bobcats are less tolerant of human activity, and become more nocturnal to avoid people. Another possibility is differing prey availability. Bobcats particularly favor snowshoe hares and cottontail rabbits for food, and the activity patterns of these species were quite similar to that of the bobcat. In the summer, fisher hunt birds and small mammals that tend to be more active during the early morning and evening, times of day we call “crepuscular”, and these prey might be particularly abundant near people.

Activity patterns for our study species during the summer in rural and exurban areas. [Poisson et al. 2023]

Still other species exhibited no significant responses to exurban development, in terms of activity level or pattern. Raccoons, for example, had almost exactly the same activity in both rural and exurban areas. As a naturally nocturnal animal, they didn’t need to shift to become more nocturnal to avoid humans. As capable generalists, raccoons are particularly adept at finding food and shelter resources in most habitats.

What does this mean for wildlife and people who now share this exurban territory? Since these species are not responding in a uniform manner, it is important to consider the impacts of development as it relates to each species separately. Especially for species that may be more sensitive to human development, understanding how species respond at the exurban level may be an early warning sign for possible population declines and conflicts with higher levels of human development in suburban and urban areas. Future research in our lab will endeavor to better discern whether these behavioral changes are indicators of adaptation or potential population decline.